CyberThreat 2019 Badge Writeup

Last year I was lucky enough to attend the inaugural CyberThreat conference put on by NCSC and SANS and it was also the first time I was introduced to interactive badges at a conference.

The badges formed the bases of a CTF, which was one of the highlights of the event as far as I was concerned. Despite a concerted effort during the two day conference, nobody was able to complete all the associated challenges before the event ended. I was pleased to find out when I completed it 2 hours after the event had ended that nobody had beaten me to the chase and I could claim the prize.

For those interested, a video walkthrough from James Lyne (@jameslyne) and Simon McNameee (@mcnamee_simon), that details the various stages, is available below:

CyberThreat 2018 - Badge Walkthrough from Helical Levity on Vimeo.

Unsurprisingly having secured a place at CyberThreat 2019 and having seen various comments suggesting that the badges were going to be bigger and better than last year, I was excited to have a play.

This year, rather than being a mere two hours late, it was a full two days after the conference had closed before I was able to complete the final challenge. I don't think I will have been the first, but nevertheless it was good fun.

What follows is a brief write up of the process followed, with much of the error excluded and much of the luck written to make it sound like I have more of a clue than I do.

The Badges

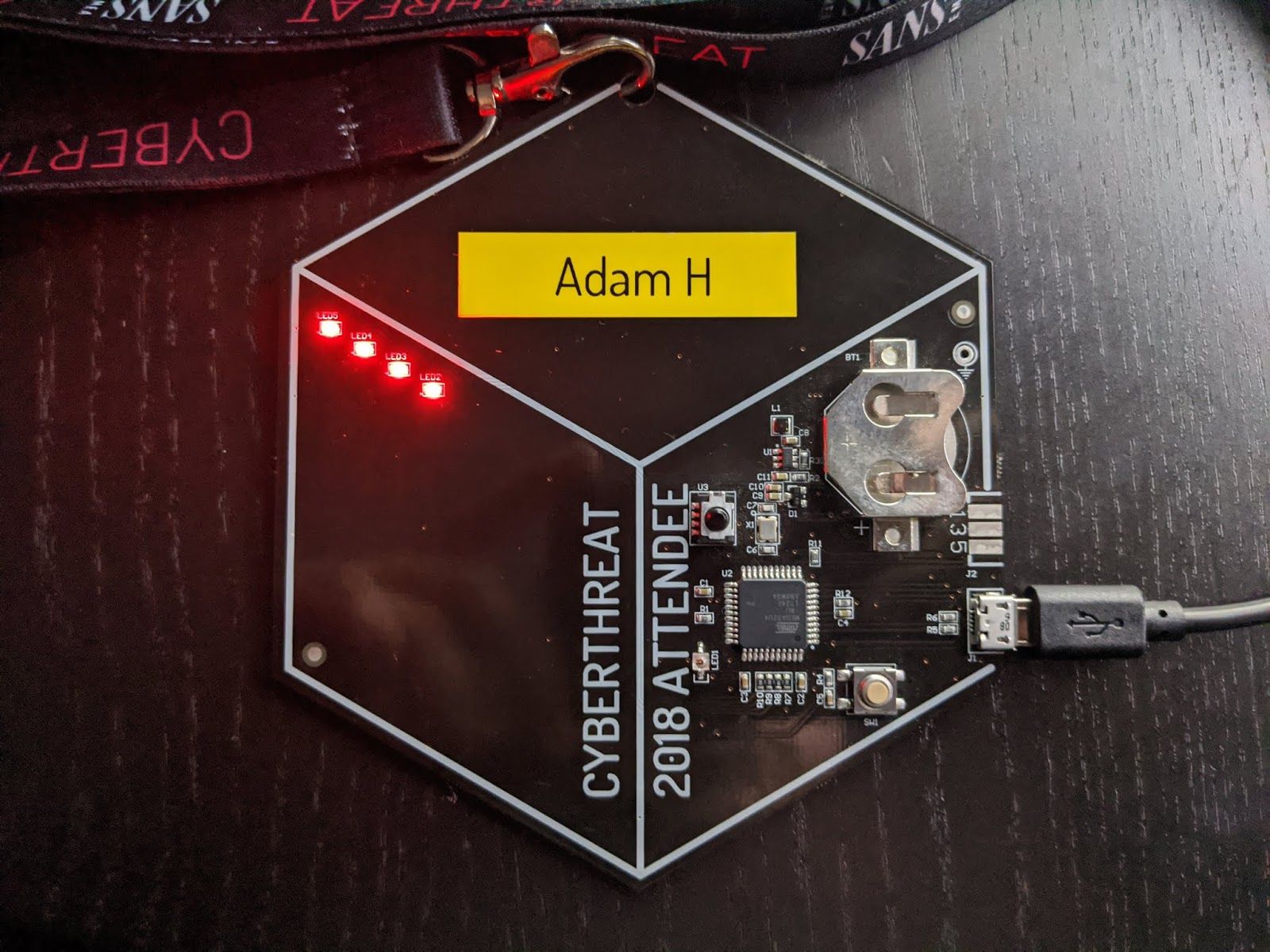

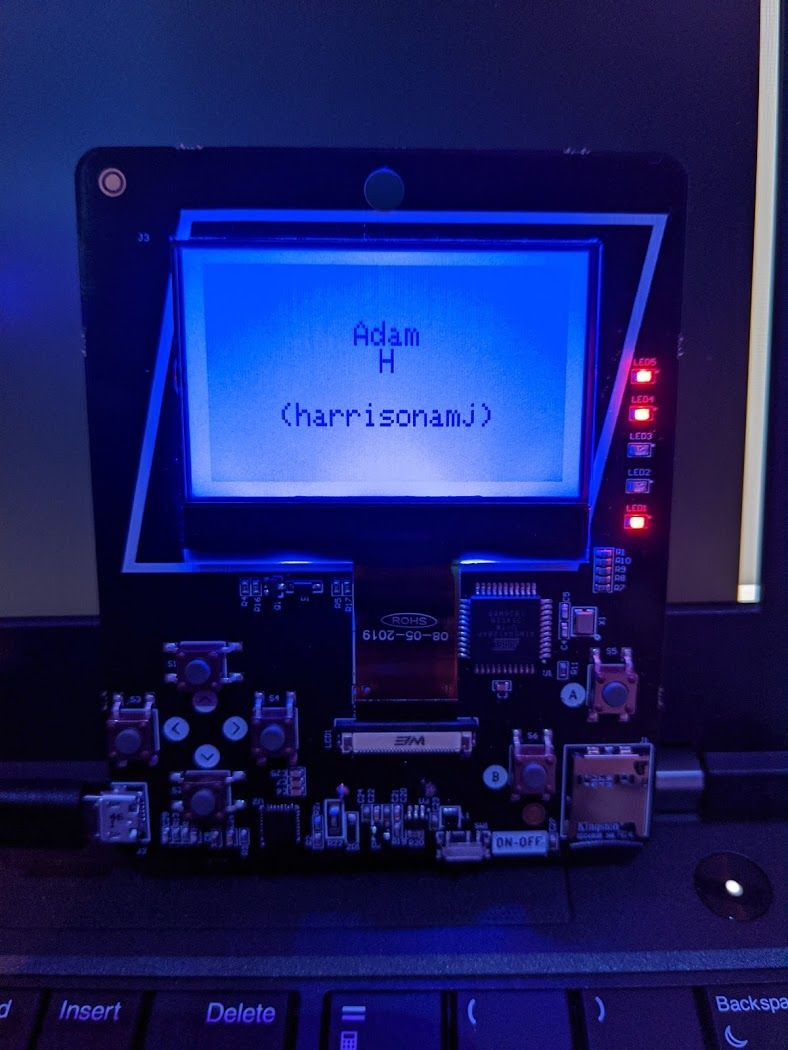

This year the badges had clearly had something of an upgrade:

The single button input and 4 LED output were now upgraded in a GameBoyesque fashion. An LCD with configurable display Name/Alias, timeout and backlight colour, as well as SDCard and multiple input buttons, made for a considerably more versatile interface for challenges.

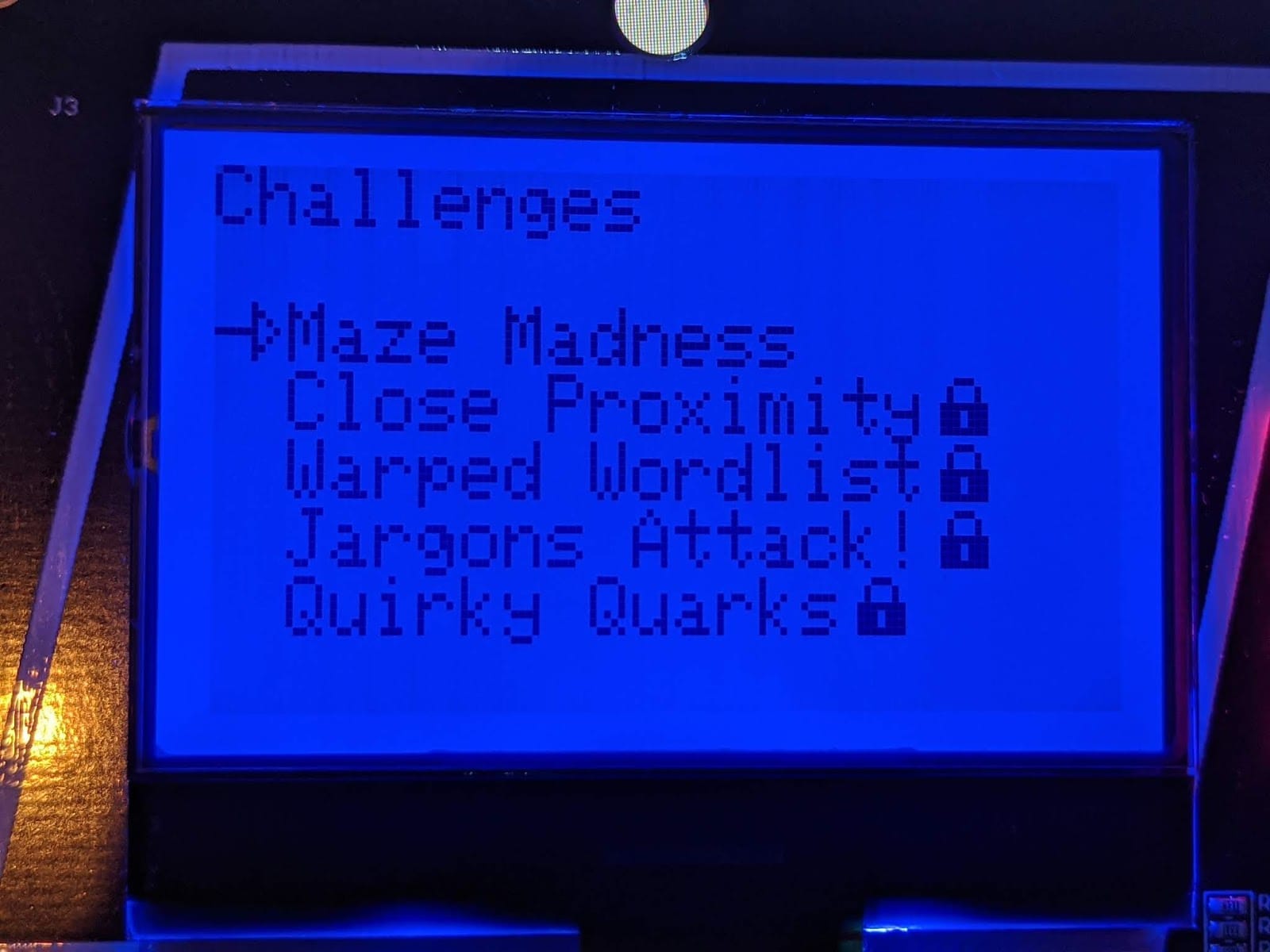

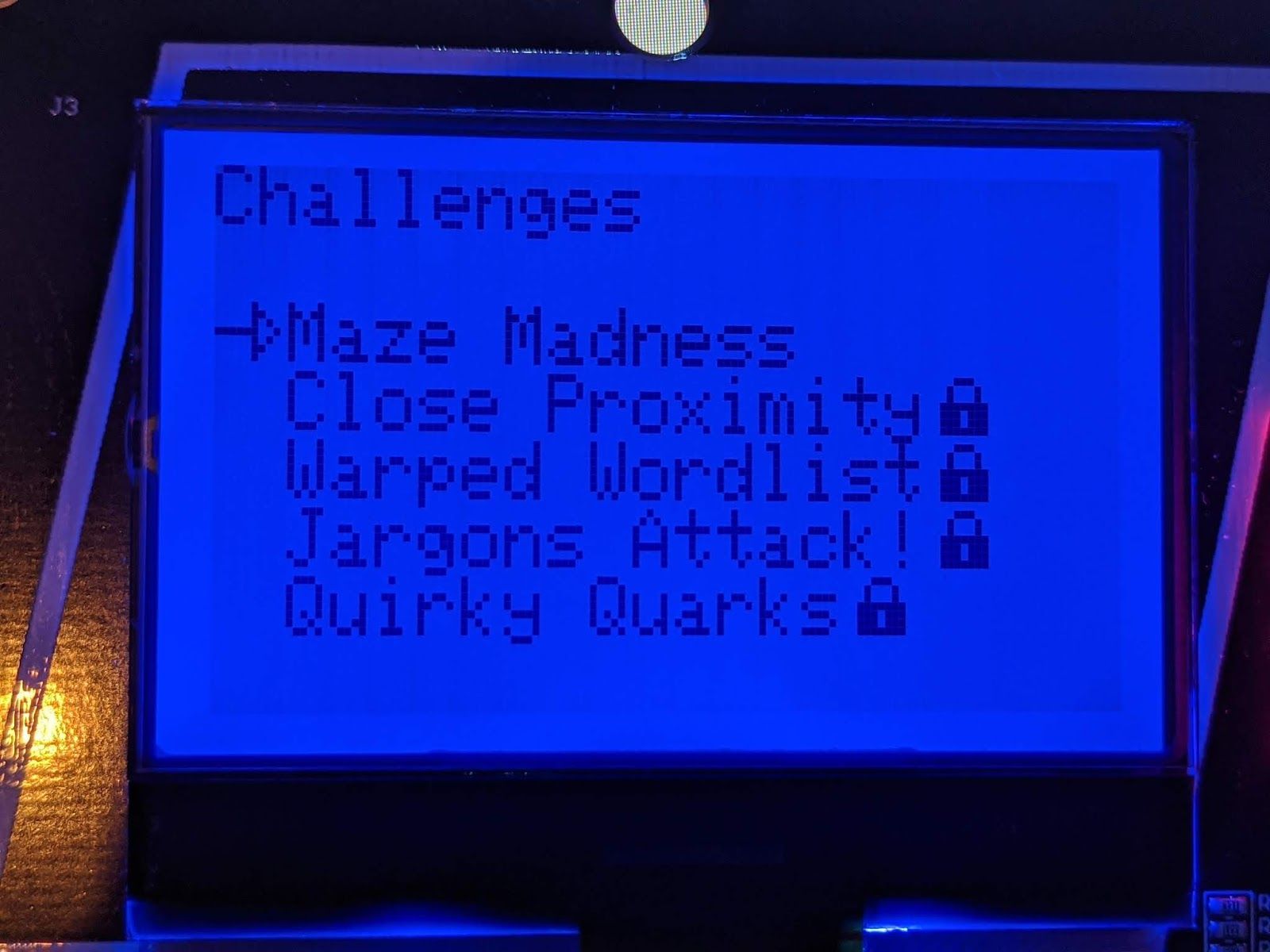

Within the device you had a basic menu which offered 'Settings' or 'Challenges', the latter of which was the CTF with 5 unlockable challenges:

Getting Started

It's probably worth pointing out that before starting the CTF, I immediately dropped the SD card out of the badge and imaged it, because I'm a forensicator and that's what forensicators do right!? But, as I had suspected it might, this proved to be handy later.

Further to this, throughout the CTF I had the badge connected via USB and was monitoring it over serial using my computer. This was based on my previous experience from last year, where all interaction with the badge occurred in this way.

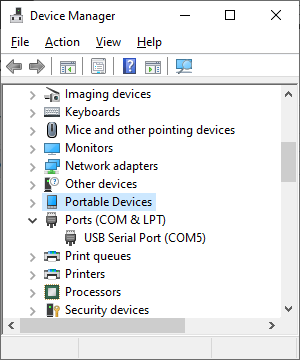

Connecting to the badge can be achieved in a number of ways but the first requirement is to identify the correct COM port.

In Windows:

Within device manager, after connecting the device via USB we can review what ports are in use:

In this case COM5.

In Linux:

There are a number of ways to confirm this but I generally grep dmesg for 'tty' after connecting the device.

dmesg | grep tty

Once we know the COM port in use we can use Putty, Arduino IDE, screen, python serial or a myriad of other methods to communicate with the badge. I found Arduino IDE with 9600 baud to be reliable for interactive needs, screen via WSL was also helpful and for later challenges pySerial was needed.

Level 1 - Maze Madness

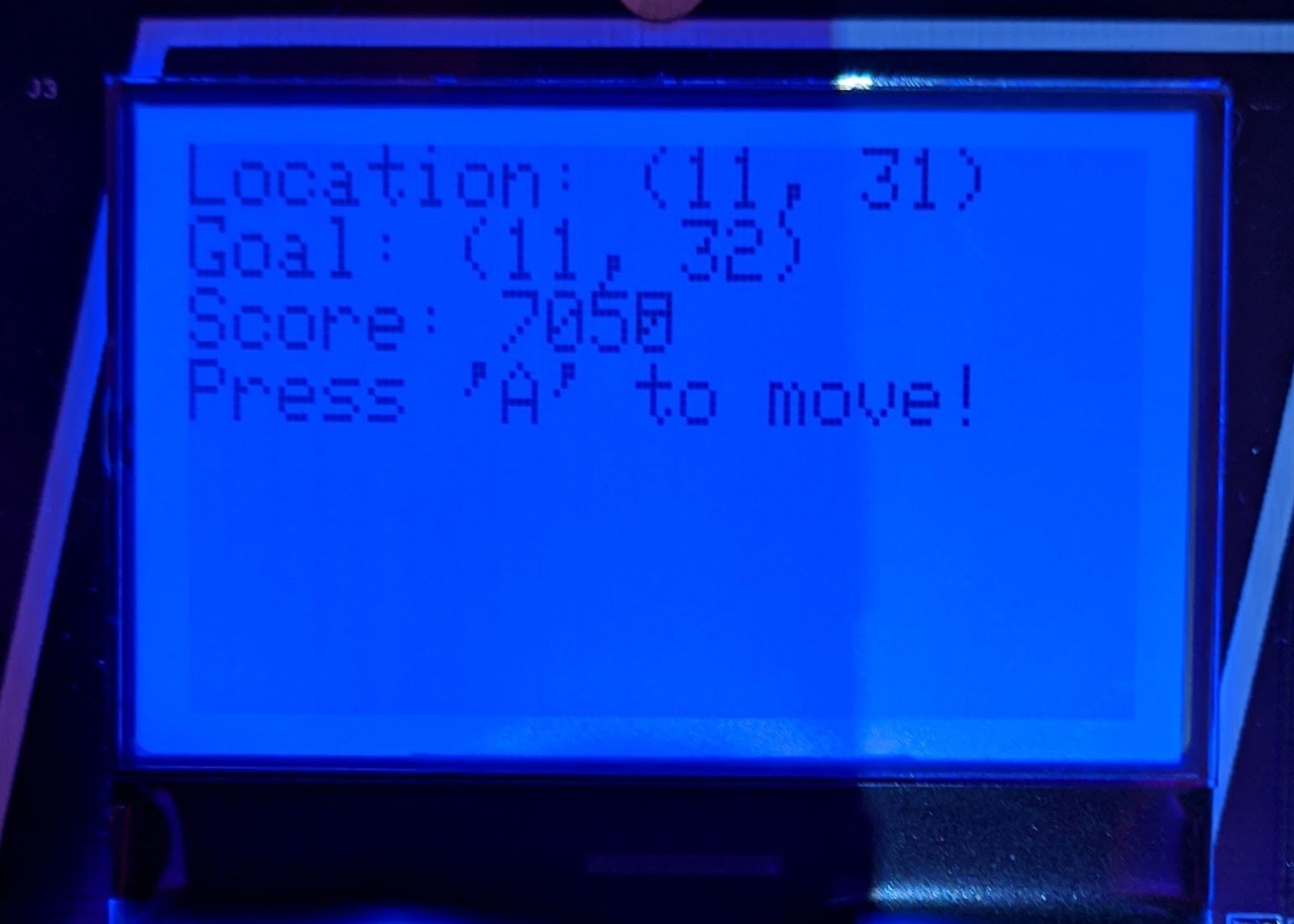

The first level 'Maze Madness' presents you with a current location, goal location, a score and the simple instruction "Press 'A' to move!".

Being the suspicious type, I promptly tried every button other than A, and quickly learned that B exited the game and no other buttons did anything noticable. I also tried the 'Konami Code' but was not rewarded with the instant win I had hoped for...

Next up I pressed the 'A' button and found that my location changed. Spamming it a few times seemed to move the coordinates seemingly randomly with any 1 press resulting in either X+1, X-1, Y+1 or Y-1. When pressing the button repeatedly it became apparent that the direction of movement was rotating North, East, South, West and that quick repeated presses and pauses could be used to move the Location in the rough direction desired.

Following some patience and luck I was eventually rewarded with my first win!

Level 2 - Close Proximity

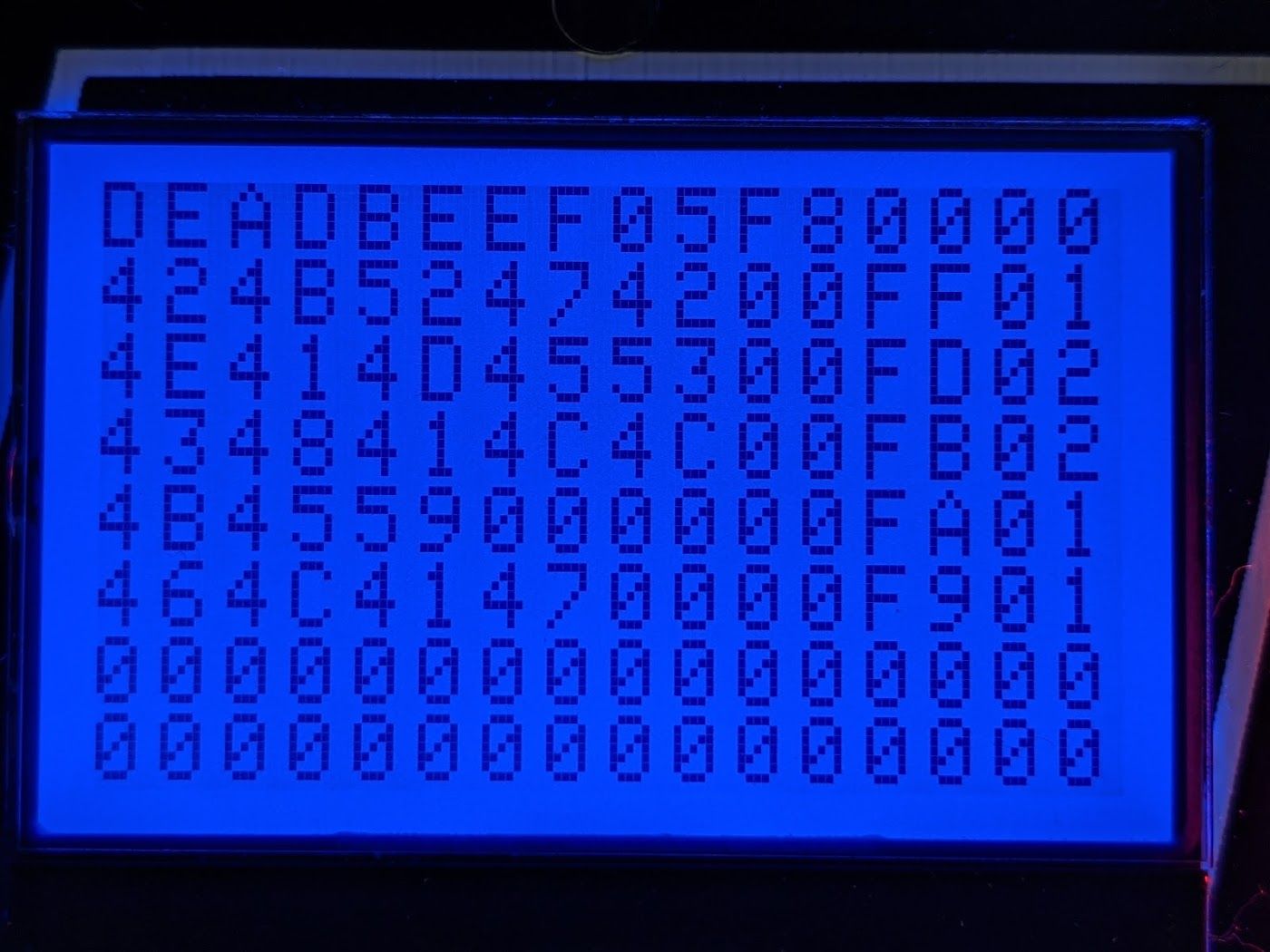

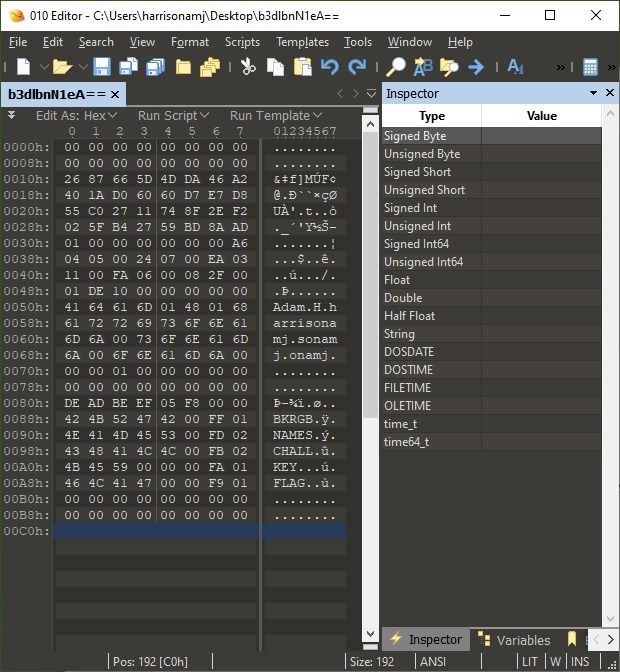

Level 2 presented the player with a scrollable wall of hex, which in the case of my badge was 3 screens worth (192 bytes).

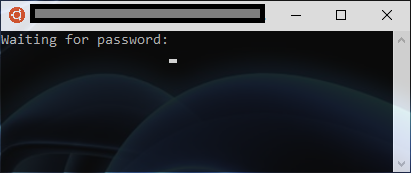

Notably we also see communication over the serial interface we are monitoring with a simple request to enter a password.

After I had recovered from the 'SEC503 flashback' that being presented with a surprise wall of hex tends to induce, I began the process of transcribing the values so I could work on determining what they represented. Incidentally, if you are a CTF author and you are considering having participants transcribe 384 characters... don't.

Once we look at the ASCII representation of the hex a few things jump out.

Firstly we can see "Adam H harrisonamj" as well as some other sub-strings of the same (presumably resulting from multiple changes to the names I configured on my badge).

We also see references to 'BKRGB', 'NAMES', 'CHALL', 'KEY' and 'FLAG'... and we all like flags. What we have between offset 80h and B0h is a "page directory esque structure"...

Challenge 2 - What if the memory is a page directory esque structure, and what if the ascii of the hex shows you the values you want... #hackablebadge #tip #CyberThreat19 pic.twitter.com/3oaKt7Ln1g

— SANS Institute, EMEA (@SANSEMEA) November 25, 2019

Based upon the need for this question to ultimately be explained to the conference, and the hints posted to social media, I think it is safe to assume this leap was not made by everyone (myself included). What I do know, is that Bastien Lardy (@BastienLardy) managed to figure it out and crack this challenge well before the big reveal, and I know this because he had to help me realise the mistake I was making...

Putting that aside if we interpret the values beside our interesting references we get the following:

| Offset | Size | |

|---|---|---|

| BKRGB | 255 | 1 |

| NAMES | 253 | 2 |

| CHALL | 251 | 2 |

| KEY | 250 | 1 |

| FLAG | 249 | 1 |

I would love to pretend that I took one look at the data and saw a the structure and it all made sense immediately but my somewhat convoluted method of getting from here to the answer was as follows.

We have a known data location, 'NAMES' which appears to populate 32 bytes and per the directory has a size of 2 and a location of 254. We can use this to derive that a size unit within the table is 16 bytes. We are going to be interested in the FLAG because this is a CTF so working from NAMES we can determine that the flag is the 16 bytes starting at 10h.

Noting that we have text input available via the serial interface we can throw that in there and quickly learn that this is not what the device is looking for...

Back to the drawing board... We also have a 'KEY' value from the table which can be found at 20h and is also 16 bytes. Things which are the same size are fun to XOR against each other right!?

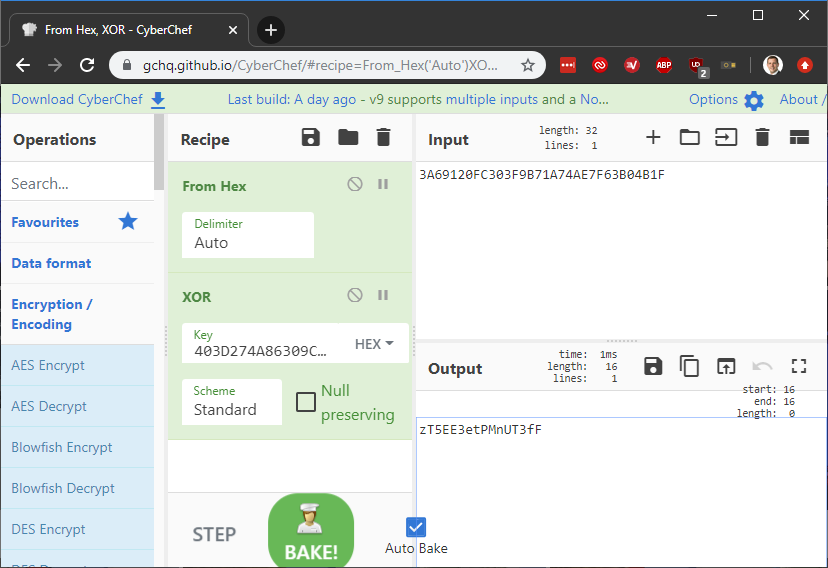

Using CyberChef we can take the 'FLAG' value, convert it from hex and XOR it against the 'KEY':

One good indication that the values you selected were correct will be that the resultant output is an Ascii string. This can then be sent to the device over serial in response to the "waiting for password" prompt and will result in level completion.

Level 3 - Warped Wordlist

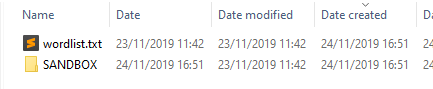

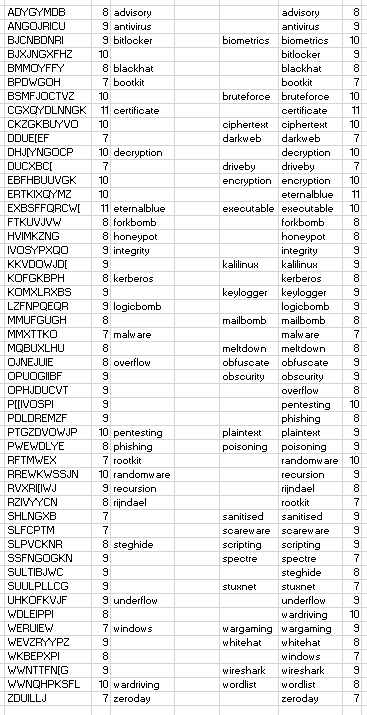

I earlier mentioned that I had imaged the SD card and had a poke around, the first thing which jumped out at me was 'wordlist.txt' at the root of the storage device. NB. no image is required you can directly access this but it never does any harm to have a full backup of the storage device.

A quick examination of the file identified that it contained a list of 50 words. Further, when I compared this wordlist with others, it appears we all had the same list.

Now on with the challenge... The screen on the device simply stated 'Password Required!' making the next step to review how the device presented over serial and see if that provided any clues:

Well I guess we better try those passwords... so type each one individually...

Alternatively we could script the consumption and sending of the wordlist using Python.

Due to the initiation of the serial connection causing the badgeto restart you either need to use the Python IDE to manually enter the commands at the right moment, or you can use a script which pauses at the appropriate moment:

import serial

ser = serial.Serial('/dev/ttyS4',timeout=1)

raw_input("Press Enter once you have reopened game")

ser.read(1000)

file = open("/mnt/d/wordlist.txt")

for x in file:

print x

ser.write(x.encode())

Unfortunately, nothing is ever that simple. The wordlist on it's own wasn't adequate. I generated a number of other wordlists in an effort to generate a "warped wordlist", this included reversing strings, converting to leetspeak, encoding the strings in various ways. But ultimately what worked was using rsmangler within Kali to generate a new mangled wordlist:

rsmangler -a -d -p --file wordlist.txt --output mangled_wordlist.txt

When the resultant list was used with the same Python script, this time we were on to a winner.

Level 4 - Jargons Attack!

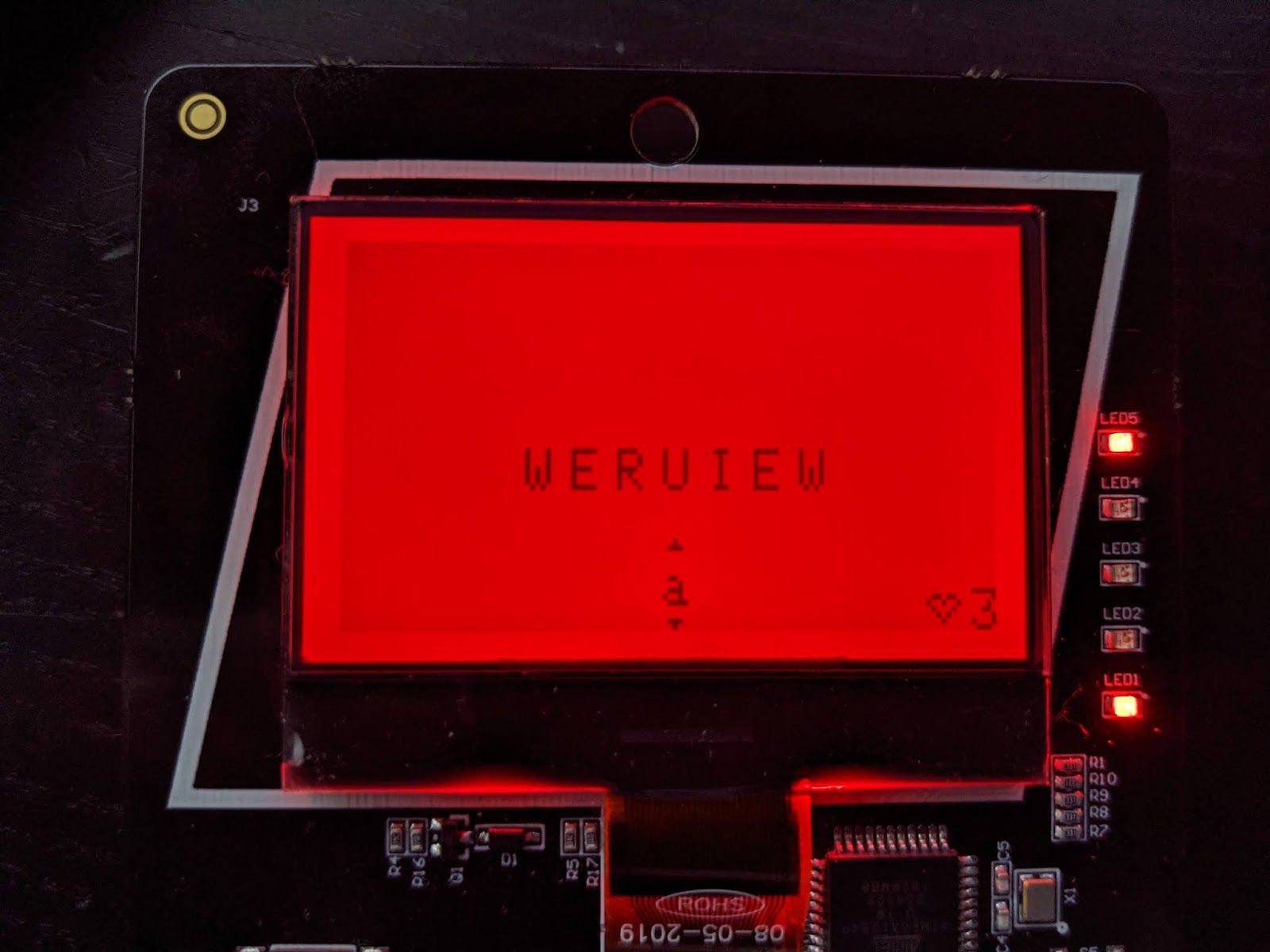

Launching the Level 4 game resulted in 'I'm thinking of a word!' being output on serial but it was obvious from the game screen that the intention was for the answer to be supplied via the device.

Each time the game was quit and restarted a new seemingly random string of letters was presented. It would see that this was a crackable code of some description.

The first task I undertook was to repeatedly open the game and start noting down the strings which were presented. After 10 or so attempts I had made the following observations:

- All 'words' appears to be roughly the same length (so far)

- All words consisted of upper case English/Latin alphabet but some also contained another character ( similar to [ )

- There was word repetition

I proceeded to patiently repeat this exercise and noted down each unique words I observed, populating a text file with the words and using 'cat | sort | uniq' to provide a master list I could check against. Ultimately I started to get close to 50 words in the list which was notable because the wordlist we have already seen contained 50 words.

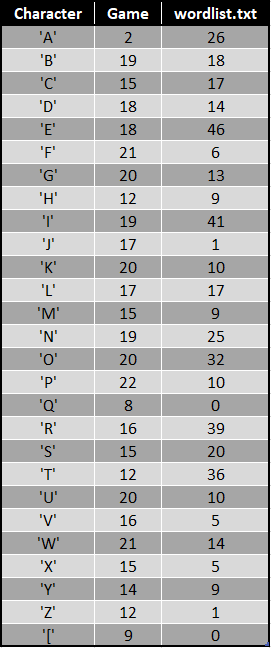

I performed a number of simple tests, which included comparing the character count between the two word lists:

This made it clear that there was not a simple character substitution going on. But undeterred I analysed the word lengths in my two lists:

awk '{ print length }' game.txt | sort | uniq -c

17 10

9 11

2 12

9 8

13 9

awk '{ print length }' wordlist.txt | sort | uniq -c

16 10

10 11

2 12

9 8

13 9

Now we are onto something... and what we are onto is the fact that I had a typo in my list...

Once that was reviewed and fixed I had a perfect match for word length distribution which was very interesting. Further when I sorted both alphabetically it became apparent that the first letter frequency was the same for each:

2 x A

5 x B

2 x C

3 x D

etc...

Next I loaded the two lists into excel side by side and using the unique letter counts within each letter set, I started pairing them up, which looked roughly like this:

There is undoubtedly a more scientific approach which would allow for the full listing to be paired up, but for the purposes of completing the game, only one match was needed so the approx 50% I had completed was more than enough.

I fired up the game again and saw that the word I was prompted with was in my new dictionary, typing in the corresponding word from the wordlist.txt file with the badge text entry method resulted in completing the level successfully.

Level 5 - Quirky Quarks

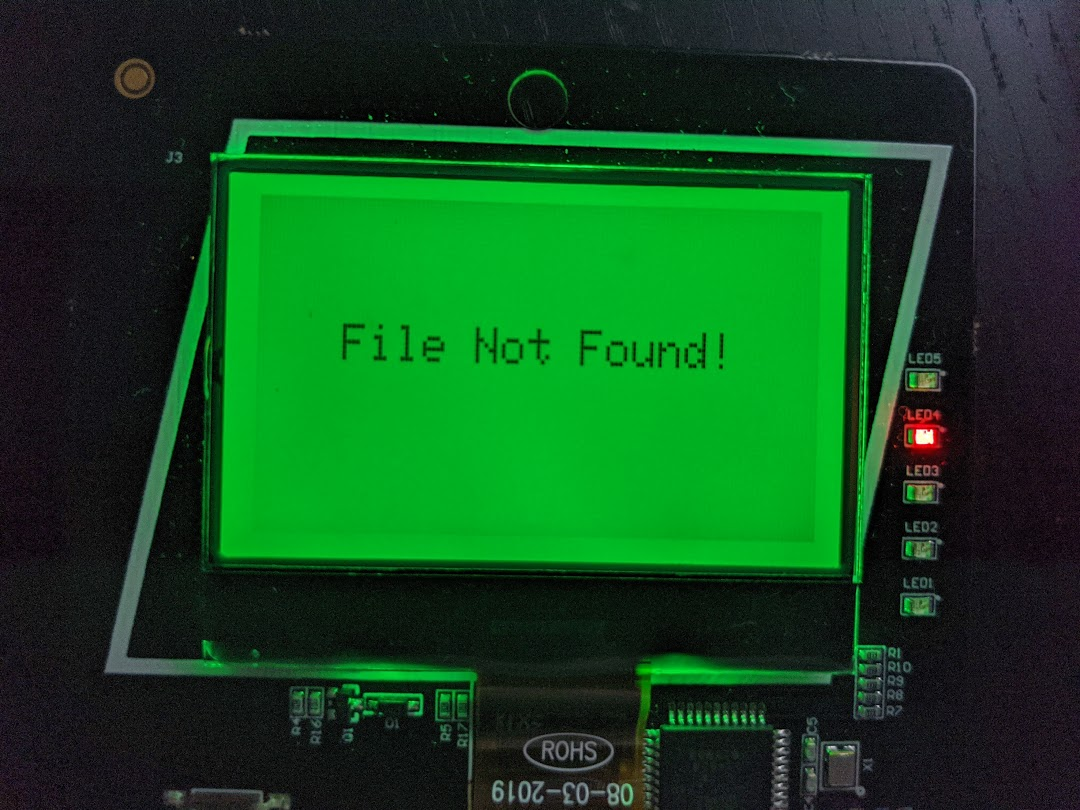

Launching this challenge you are presented with a 'File Not Fount!' error on the screen of the device:

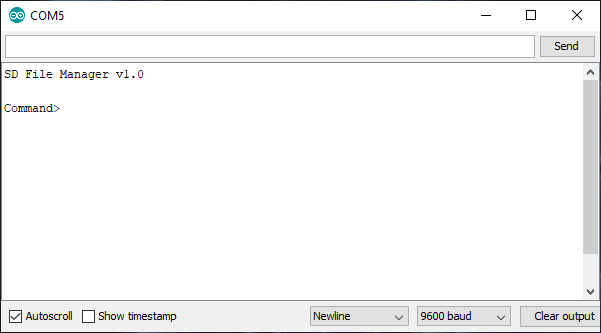

But more notably, over serial we get:

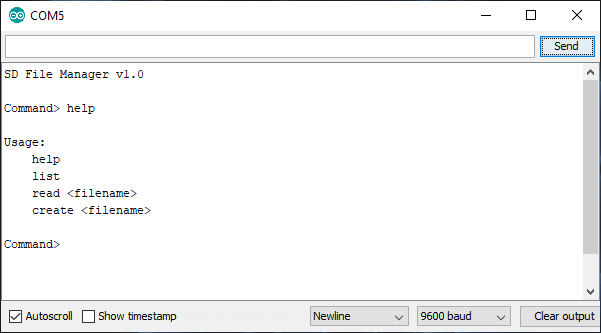

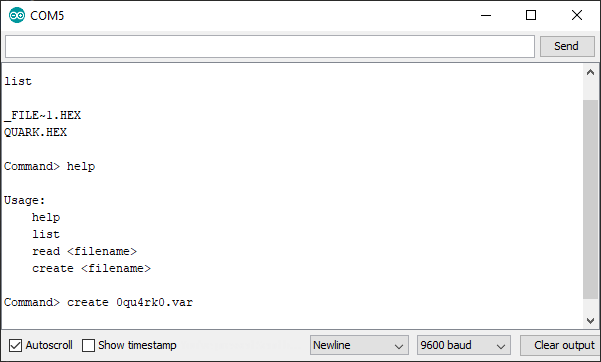

After initially throwing a few commands such as 'dir', 'ls', 'flag' etc I finally swallowed my pride and tried 'help', which was helpful:

As with Level 4, when spelunking through the SD card I had already noticed something notable again I had already stumbled upon a component of the game earlier. So it was no surprise when I selected the list command and saw 'QUARK.HEX' which I had already had a play with. I also noted a file named '_FILE~1.HEX ' but this turned out to be a red herring.

I had already copied QUARK.HEX from the SD card earlier and noted that it was an ASCII file containing HEX values and that the first characters were '7f454c46'. You can even use the inbuilt 'read' command to establish this. '7f454c46' is the file signature associated with an ELF executable so if we exported the ASCII content of the file and interpreted it as hex it looks like we would have an ELF on our hands.

I am sure there is a jolly clever way to do this on the command line, but I opened up QUARK.HEX in Sublime Text, copied the contents and pasted into 010 using the Edit > Paste From > Paste from Hex Text feature.

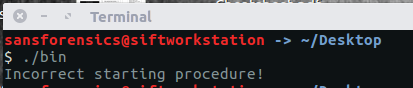

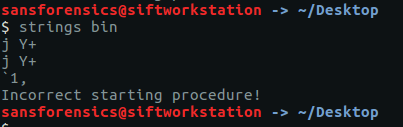

Once I had saved this out (in my case named 'bin') I had an ELF which I could execute. So I did:

Obviously it wasn't going to be that easy. So I undertook my traditional 3 stage reverse engineering process:

- Use strings

- Open in IDA, cry and promptly close

- Ask Charlotte (@gh0stp0p) to do it for me.

Strings wasn't giving up any clues:

IDA had the expected result:

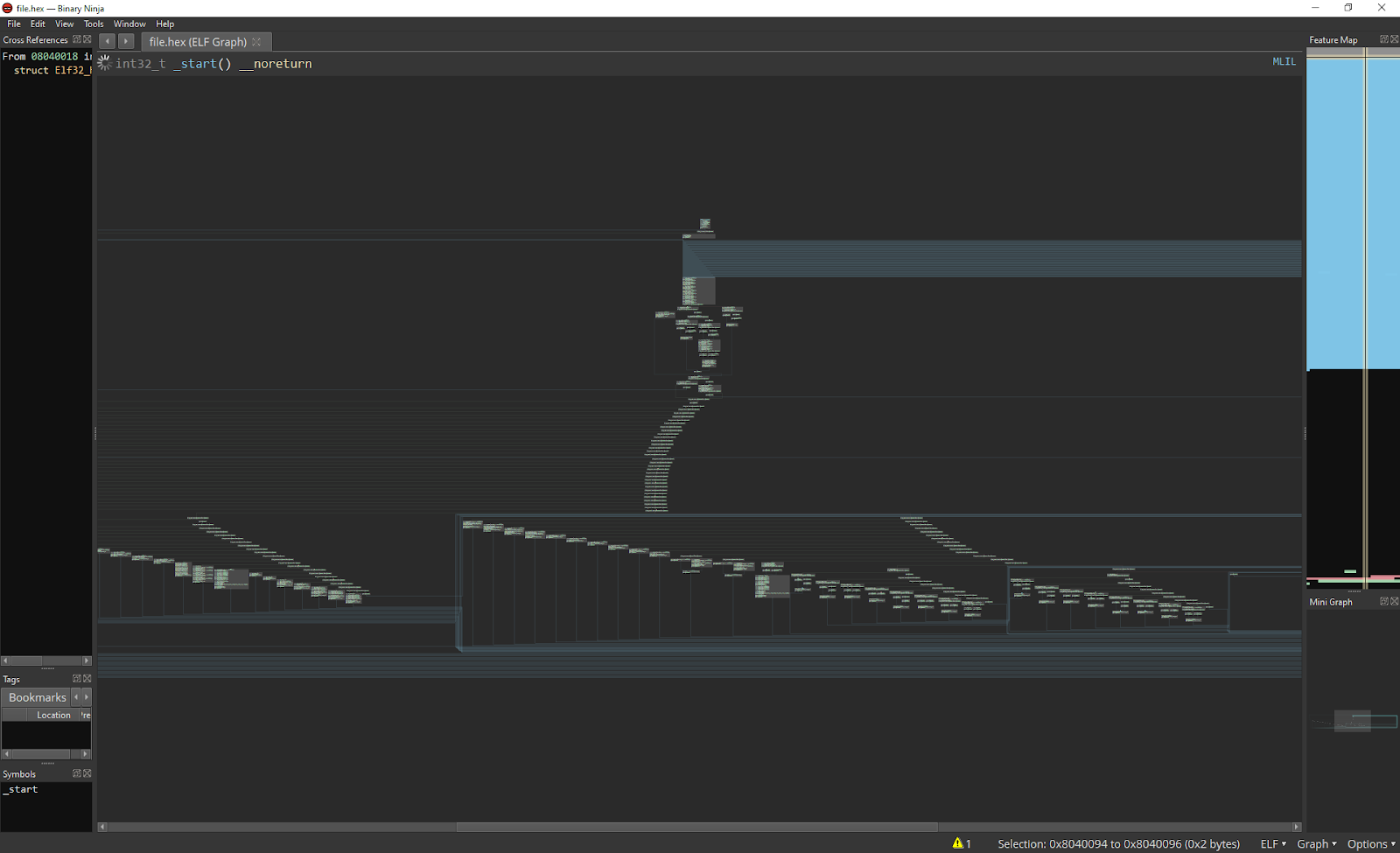

So did BinaryNinja:

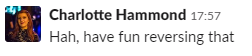

But the real kicker was when my go to backup option went as follows:

Reverse Engineering is very far from my strong point, and as such a lot of guess work occurred. I persisted down all conceivable rabbit hole until I settled on the fact that I would have to work with this binary somehow. I ran the executable within gdb and determined that despite no effort to learn since I last tried to use gdb I still have no clue what I am doing.

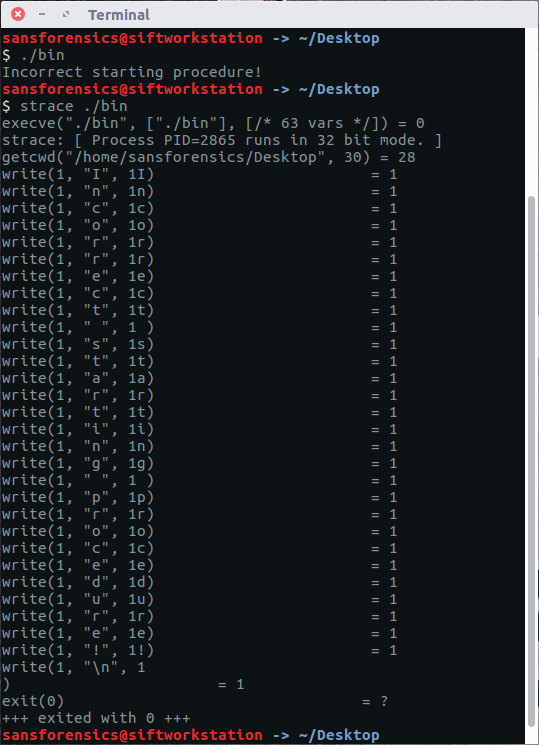

A quick strace to see what was happening before the error resulted in the following:

What we see in the first line before the error is printed is the use of 'getcwd' to fetch the current working directory. I'm not going to lie, this may he the case in every program but it got me thinking that the executable may want to be run from a certain location.

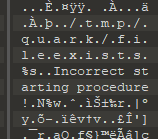

Looking back in the hex of the file we can see what looks like a file path, towards the end of the file. This was missed when we ran strings earlier due it the encoding.

If we run strings again we can pick out the unicode string by adding '-e l':

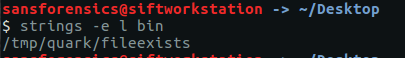

So we create the requested directory structure, move the executable 'bin' into it and run it from there using the below commands:

mkdir /tmp/quarkmkdir /tmp/quark/fileexistsmv bin /tmp/quark/fileexists/cd /tmp/quark/fileexists/./bin

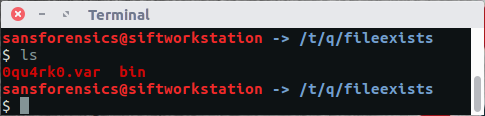

We note that we do not get an error, and if we 'ls' the current directory we have a new file:

Ultimately this is an empty file. But all that matters is the filename. I proceeded to copy the file, preserving it's metadata into multiple locations on the SD card in an effort to see if it's presence would cause a win state in the game. However, subsequent testing shows it is as easy as using the file manager tool within the badge to create a file of that name...

And...

Massive thanks to the guys who put the effort into the badges this year, it made for a fun challenge and I've been inspired to do some playing on the firmware side to see what can be achieved.